„La ballade des gens heureux“, Film shooting in Carcassonne 2001

“La balade des gens heureux” (The Ballad of Happy People)

Participants: Frédéric Auvrai, Lisa Biedlingmeier, Martin Haak,

Nathalie Karanfilovic, Samantha Scott.

Installation for the Opening Exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo, Paris; 2001

Movietrailer:

Alexander Györfi – Pimui Pictures:

“La balade des gens heureux” (The Ballad of Happy People)

Participants: Frédéric Auvrai, Lisa Biedlingmeier, Martin Haak, Nathalie Karanfilovic, Samantha Scott

"La ballade gens heureux"

Mitwirkende:

Frédéric Auvrai,

Lisa Biedlingmeier,

Martin Haak,

Nathalie Karanfilovic,

Samantha Scott.

Pimui Pictures "La ballade gens heureux" ist ein Projekt, bestehend aus mehreren Teilen. Ausgangspunkt ist Györfis Schallplattenaufnahme aus dem Jahr 2001, eines Soundtracks, zu einem fiktiven Film. Neben der CD existiert ein Filmplakat und ein 3 minütiger Movietrailer. Desweiteren eine Photo- und Filmdokumentation, über die Filmaufnahmen des Movietrailers in Carcassonne. Györfis Interesse gilt den Nebenprodukten, die bei einer Filmproduktion entstehen. Der Film, als eigentliches Zentrum entsteht nur in der Vorstellungskraft eines jeden Betrachters. Die Einzelteile formen individuell verschiedene Spielfilme.

Palais de Tokyo-Site de creation contemporaine,

Paris 2001

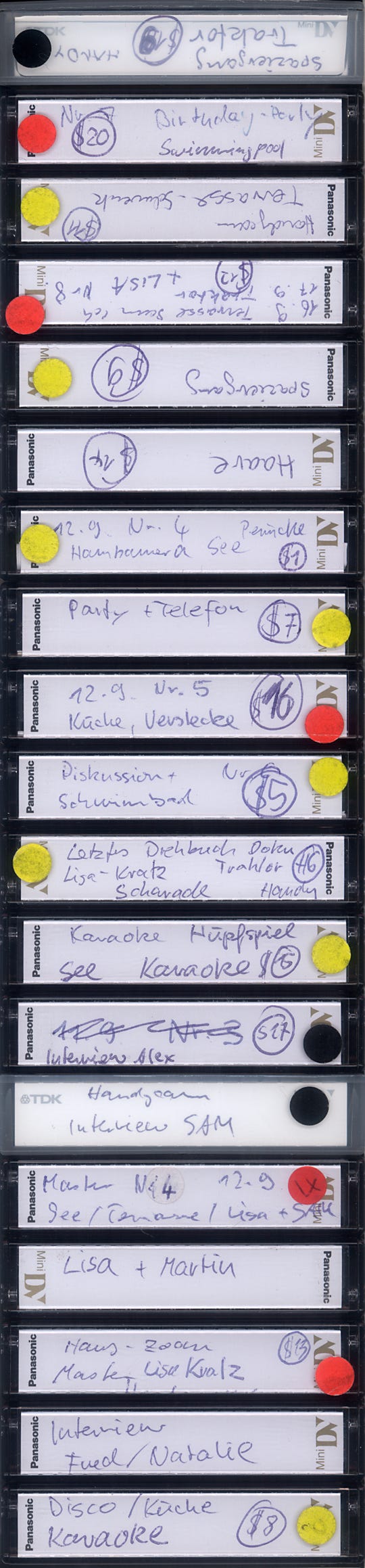

Video stills: „La ballade des gens heureux“, Film shooting in Carcassonne 2001

Interview von Philipp Ziegler zu dem Projekt "La ballade des gens heureux" 2001

Alexander Györfi – Pimui Pictures:

“La balade des gens heureux” (The Ballad of Happy People)

Participants: Frédéric Auvrai, Lisa Biedlingmeier, Martin Haak, Nathalie Karanfilovic, Samantha Scott

Music occupies an important place in the work of Alexander Györfi. The artist, who lives and works in Stuttgart and Berlin, founded the music label “Pimui,” under which he has carried out several projects since 1997.

In these Györfi has confronted the mechanisms involved in producing music and more recently film. He frequently refers to the stereotypes of the professional music and movie market, as in his fake production of an MTV music video that at first glance hardly stands out from its professional models, despite a minimal of input by the artist in filming and editing. While affirming his fascination as a fan, Györfi is attempting here to think critically about Pop culture phenomena taken as examples in his work. In the process of transposing his participant-based pieces, Györfi generally furnishes only a structural framework, within which those taking part—most often they are friends or close acquaintances—can freely act and develop the givens of the artist’s initial conception as they see fit.

In the fictional recording studio set up in the Ludwigsburg Kunstverein, for example, he invited the participants to make interactive use of the equipment that he had placed at their disposal. More than in the idea of creating a finished product in the form of a recording, a product that is meant to be saved, the artist’s interest lay in the exchanges and actions that took place alongside the process of recording music.

For Györfi, this strategy of working in collaboration is, in each instance, an opportunity to think about the means of transposing into a visual field of art the communication processes that are put in play in the spheres of music and film. Through the form of the installations’ presentation, he frequently offers audiences the possibility of involving themselves in his works. By way of his “lounge”-like arrangements, Györfi aims above all to create (free) discoursive spaces in which the public can react to the artist’s offer however they want to, or use the given situation to cultivate exchanges. His work has progressively opened up to the design of ensembles/seats whose form and function are exactly adapted to the situation of each exhibition.

Philipp Ziegler: Your new film, “La balade des gens heureux,” took shape in a vacation home in the south of France. Where does the idea for this project come from?

Alexander Györfi: The idea of shooting a film has haunted me for a long time. That began in 1999 with a project at the Wolfsburg Kunstverein. At the time, I was already preparing a record and I had been very interested in film soundtracks. The idea for my piece in Wolfsburg was to take scenes from films that I liked and to insert my own music. One day I finally wanted to produce a film myself for my own soundtrack. Obviously the idea for me wasn’t to shoot an entire fiction film; rather it was the products normally linked to a film that interested me: soundtrack, trailer, the poster advertising the film.

PZ: Did “La balade des gens heureux” take shape around the musical theme of the film’s soundtrack.

AG: I did indeed produce the soundtrack before the film, but my priority isn’t to transpose a musical idea into images. What interests me most is the mechanisms at work in movies, the film’s different modes of expression. It is the strategies and products of the film’s commercialization that seem important to me here. At heart the question that really preoccupies me is how does film function in general. In earlier works, I had already confronted the question of how music is created, produced and put up for sale, what images play a part here. In the music video for “Boys Don’t Cry,” for example, an MTV logo appears as a dissolve, which suggests to the observer that what they’re watching is a professional video of a real group. I transposed the analytical approach of that work to the business of film.

PZ: Does the concrete action of the film become purely secondary at that point?

AG: It’s like when you make music. For the video “Boys Don’t’ Cry,” I began to wonder how a commercial hit might be presented, what is particularly important? But then, when you start, when you make music yourself, it’s your musical ideas that count and nothing else. You’re aware of harmonies, melodies and sound. That’s much more a question of intuition. That’s also what happened with “La balade des gens heureux.” The starting point was my theoretical interest in the mechanisms of commercial cinema, but as the project shapes up, when the camera begins to roll, it’s the content that comes to the fore. What counts then is what you want to say in the film.

PZ: In your projects, you always allow the musicians and actors a large amount of freedom. Is the finished product less important to you then than the processes that take place during the group conception of the piece within the framework that you provide?

AG: There are some artists who prefer to stay in their studio. For me it’s more important to work with other people, to create areas where communication can take place. I can only accomplish that by making proposals and offering conditions/frameworks that others can use. That’s expressed in different ways. It can be a home page where people send their own contributions; it can also be a recording studio or, as is in this case, a setting for a film. Generally the structures of my works are always very open. The idea of the label, which runs throughout all my works, represents this structure. That label enables the people I’ve invited to take part in my pieces to better identify who they are. There’s been the Pimui-Mobilstudio in Ludwigsburg, the Pimui-Telemusic for Tokyo TV, and the current film production company is called Pimui Pictures. The name already has to announce the specific form of organization in my artwork. I’m not the sole artist. On the contrary, as much as possible I want to integrate the participants equally. This way of working offers me an alternative to the artist’s traditional role. Thus Pimui can be conceived for the greatest range of projects. In the concrete case of this film, it so happens that three days before shooting was to start, my main actor dropped out. With that, the scenario no longer made sense. So the actual shooting of the picture was carried out in an impromptu manner and the scenario took shape during discussions in the group. It was often the group that decided what was to come next. I was only the master of ceremonies who guaranteed the framework, that is, the location, the transportation and the financing. So six friends go to a house and try to shoot a film. Using a second camera, I attempted to document the different phases of the project. It was precisely the documentary camera, which was not important in fact to the film’s action, that eventually played a decisive role in the story’s development, since fiction and reality little by little began to merge in the end. Only from that point on did the action of “La balade des gens heureux” begin to take concrete form.

PZ: What is the film about?

AG: The film’s action is told from the perspective that is the result of combining film and documentary material. To begin Fred says, “Now it’s my turn to tell the story. The others have already told their version.” That serves as the trailer’s narrative thread without Fred concretely saying what happens in the film. I think it’s a shame when a trailer reveals too many things. You don’t know in this case whether Fred is seated in a psychiatrist’s office or a police station. He says that he accompanied his girl friend to a treatment center where there were other persons, whose problems are not specified. Then he tells how he saw the group, and talks about the dynamic of this group in the house.

The object of the project then merges with the content of the trailer, the documentary camera functioning here inside the framework of the film’s content. Fictional scenes are shot of course, but basically they are very much a part of reality. A lot of the film is about the connections between persons, the relationship of the group’s members among themselves, but also the possible solitude and isolation of each. When you share such intimacy over two weeks, as we did during the weeks we were shooting the picture, that automatically begins to look like group therapy in certain regards. Since that wasn’t a dominant aspect of the scenario, the documenting of our reality and the fiction of the film were able to merge without a problem.

PZ: In the case of the exhibition, you try to integrate your videos in the space as a kind of installation. What is important for you in the presentation of “La balade des gens heureux?”

AG: I would be interested in showing the film in a normal cinema as well, in order to allow it to function as the film trailer it claims to be. That would be the ideal form of presentation. In a museum, it’s important to show the film in such a way that the space functions as a movie theater. You couldn’t show “La balade des gens heureux” on a monitor. Excerpts of the music that I’ve written are already included in the trailer. You can listen to the entire soundtrack with headphones in a kind of Listening Lounge and complete the scenes from the trailer or create your own film yourself.

The film is only a proposal made to the observer, it doesn’t exist in the sense of a fixed narrative. The end is left completely undefined. There are of course key images, but not like in commercial cinema where it’s simply a matter of consuming images from the film. Indeed, it’s also quite possible to use the soundtrack to observe people at the exhibition. In that case, the film has more to do with the reality of the visitor to the show.

PZ: Already in the past you were always making a lot of music on the side with different groups, big bands, orchestras and even as a DJ. How has that had an impact on your artmaking?

AG: In the past, not managing to bring together art and music in my artistic approach posed an enormous problem. On the one hand, there were the groups I was playing with, on the other, I was alone at home in front of my canvas and I would paint. The two things had nothing in common. Today that’s no longer a contradiction for me; indeed, it’s very important for my artwork. A good number of things, like this project as well perhaps, spring from the aspiration to found a group. This project very much reminded me of our earlier dreams of making music with friends. You would think about who could play which instrument. Maybe you didn’t know yet how to play the instrument in question, or not very well yet, but basically that didn’t matter. What was in fact going on was that you were giving a form to something inside that group. You had a certain idea of a group and you tried as best you could to make it concrete. That’s more or less the same thing in the situation of this film, the film crew as a group. They’re not professional actors, just as the cameramen are not professional cameramen, but each person chose a role with which they could identify and which amused them. Since there were no predefined roles, each could also largely play their own identity. “La balade des gens heureux” is also a group portrait then. I don’t know from what moment on an actor becomes professional. Doesn’t an actor also only play the role of an actor?

PZ: What place does friendship take up in your work?

AG: I think friendship might be written out as a title above my work, even now in the case of this film project. In my work, exchanges between people are very important in order to arrive at something together. That works well with friends, but also with strangers. Above all it’s a question of creating a social framework that enables communication.

PZ: Just how far do your films aim to be a critique of commercial structures?

AG: For me it’s not about criticizing Hollywood or recording companies. My artmaking must allow me as much as possible to create my own countermodel. To that extent, there may indeed be a critique in part by showing how things can work differently, when they are not legitimized by the economy alone. It’s a fascinating phenomenon that music groups still exist. I mean groups that make music from pure idealism, without worrying about being discovered and becoming rich. On the other hand, you see those television shows that classify people by categories. They have a gigantic music industry at their disposal that allows them to put new tunes on all the radio stations. It’s surprising to see how that works so well. And all the more important to show what’s still possible beyond concerns about making money.

Interview: Phillip Ziegler

Exposition collective

VIRGINIE BARRÉ + CHRISTOPHE BERDAGUER & MARIE PEJUS + ALAIN DECLERQ + WANG DU + MICHAEL ELMGREEN & INGAR DRAGSET + NAOMI FISCHER + GELATIN + SUBODH GUPTA + KAY HASSAN + ALEXANDER GYÖRFI + GUNILLA KLINGBERG + SURASI KUSOLWONG + MICHEL MAJERUS + PAOLA PIVI + MATTHEW RITCHIE + FRANCK SCURTI + SISLEJ XHAFA + JUN’YA YAMAIDE

Cette exposition, qui réunit les œuvres d’artistes émergents sur la scène internationale, ne souhaite pas les placer sous l’enseigne d’un thème spécifique, et il ne s’agit pas, non plus, d’une succession de petites expositions personnelles. Ces choix d’œuvres et d’artistes annoncent plutôt les grands axes de travail du Palais de Tokyo pour les années à venir.

Ces artistes, qui s'expriment aussi bien à travers la peinture, la vidéo, la photographie, la performance ou d’autres médiums, dessinent tous une esquisse du paysage artistique actuel et mettent en jeu certaines des problématiques majeures de l’art contemporain.