"A-side: China Girl" mit Friederike Kempter and Jean Gid Lee. Filmshooting Torstrasse. 2003

Installation View: Play- Gallery for still and motion pictures, 2003;

"A-side: China Girl". Starring Friederike Kempter and Jean Gid Lee; Video 6:50 min.

Friederike Kempter and Jean Gid Lee;“ Berlin/Schöneberg Haupstrasse" Bowie lived here,..

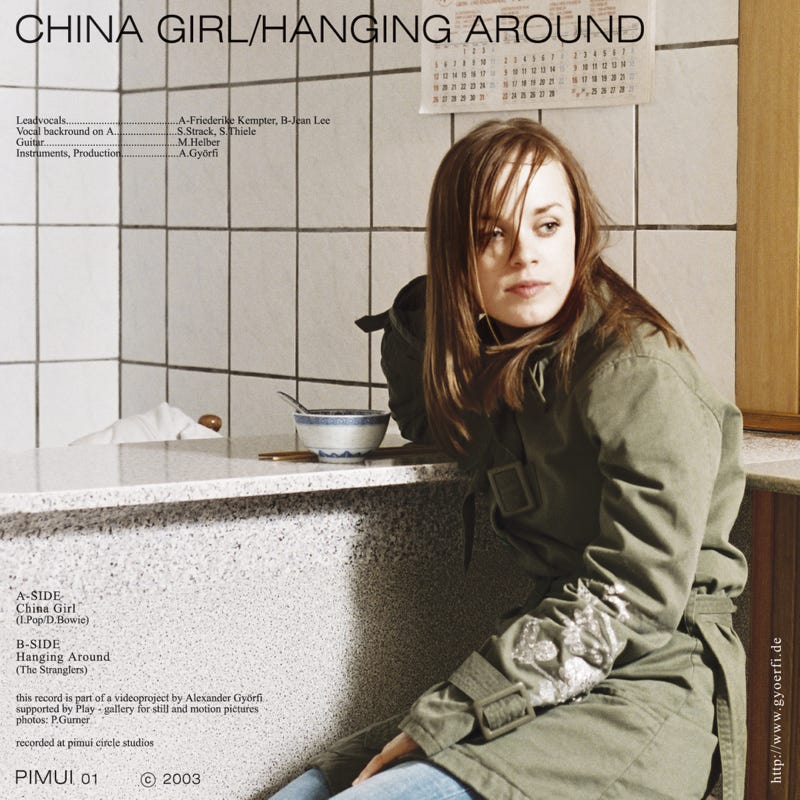

7’’ Cover

„ A-Side; China Girl“

Mit: Friederike Kempter und Jean Gid Lee

Halvor Kyrre Haugen and Öystein Aasan (in Neue Review Juli 2003 )

"A-side: China Girl" Starring Friederike Kempter and Jean Gid Lee

Play- Gallery for still and motion pictures, 2003

The Artist as if

A music video is central in Alexander Györfi's exhibition titled "a-side China Girl" at Play Gallery. Presented within a smoothly designed space filled with plywood boxes and white canvas that covers the walls. Two scenes of narrative are central in the video. One in which the lead singer is practising or recording what is to become the full-length music-video version of "China Girl" (originally written by Iggy Pop and David Bowie and performed famously by the latter) In the second scene, the singer is hanging around in an Imbiss, with her counterpart in the movie, "the China Girl". They are taking on roles in front of the camera, dancing and singing along to a snappily produced version of "China Girl". The most interesting point is exactly this shift in roles and scene. The rehearsal scene is just as acted out as the main music video part. From what Alexander Györfi has said about his strategies in film making, it seems as if the camouflage has dropped and we are able to see the fiction even clearer then before.

Testing: 1 - 2 - many texts Backdrop 1:

The Artist as Producer

In his text the Artist as Producer, first published in 1978, Dan Graham presents a compressed history of Pop-music. The title of the text alludes, of course, to Walter Benjamin's 1934 lecture the Author as Producer. The word producer does not, however, have the same meaning in the two texts. In Benjamin's text, it refers to a social identity, defined by its position within the production apparatus, and that ultimately has the proletarian worker as its real referent; in Graham's text, the word denotes a professional title – the producer of the music business. What the field of music offers Graham, as an artist, is an alternative model of art production in which not the immediate producer (the stupid painter) but rather the mediator is the true creator. The protagonists that incarnate this producer in Graham's narrative make up a paternal line of "urban Jews" that culminates in the coming of Malcolm McLaren – the demiurgic orchestrator of the pop spectacle who cleverly pulls the strings from behind the scene, making the popstar, a product of his own making, dance like a little homunculus. It was Benjamin's imperative that the work of the author as producer should have the character of a model. For Benjamin, this meant that It should have the power to mobilize its audience into a kind of co-productive consumption. And: it should serve as an ideal for future works. Graham's text, the product of his practice as an artist as writer, served as a vehicle for Graham's redefinition of his own professional identity. In this sense, the text may be said to have worked as a model both in a descriptive and a prescriptive way: the text is an allegorical self-portrait, written by an artist who reflects on his status as an artist, and who constructs his artistic identity as he writes. Györfi has for some time worked with music and strategies connected to music production to produce installations, paintings, records and Internet sites. Through different forms of collaborations, lack of one author and playfulness, he has made user-friendly projects where the visitors were included to a large extent. His work may be seen, not as much as a critique of institutions, but as a result of the evergreen longing to join your mates in a collaborative rock n' roll band.

Backdrop 2:

The Artist as Post-producer

In the nineties Nicolas Bourriaud coined the term Relational Aesthetics, which, in competition with the labels Kontext Kunst and New Genre Public Art, seems to have gained the upper hand as the ultimate toe-tag on the corpus of the last decade's social art practices. Last year, Bourriaud upgraded his account of the state-of-contemporary-art for the new millennium under the label Post-production. The stable of endorsed artists remains for the most part the same: Tiravanija, Gillick, Huyghe, Parreneo, Gonzales-Foerster, and Cattelan. But this time around, the social-talk is traded in for a harder currency: an "audiovisual vocabulary used in television, film and video". Like the computer programmer or the Deejay, the artist as post-producer "samples", "dubs", "recodes" and "reprograms" the givens of culture: „preexisting works or formal structures". Ultimately, the artist as postproducer controls the switches on the grand console of culture plugged into the power station of the real: s/he is a "remixer of realities". To Bourriaud's mind, the artist's installing him/herself in this undeniably privileged position does not expose him/her to the corruptive effects of power. The artist's integrity is apparently guaranteed by his/her simultaneously also being a consumer: Here, Benjamin's demand may be heard echoing in Bourriaud's argument –filtered, as it were, through the Original Dunlop Cry Baby® wah-wah pedal of Michel de Certeau: "[the artist as postproducer] contribute[s] to the eradication of the traditional distinctions between production and consumption". The equation production=consumption (and vise versa) is the formula that enables art to establish itself as an alternative to the „passive culture" of mass consumption. Thus, „art represents a counterpower". And, what is more, this magic formula also ostracizes the despotic Auteur to the barren provinces of Tomis. O, happy day! Democracy reigns in the Republic of Art – in Bourriaud's conception, a flat little non-hierarchical place, kind of like the state of Denmark. In her review of Simone Weil's "Selected Essays" in 1963, Susan Sontag wrote: "Perhaps there are certain ages which do not need truth as much as they need a deepening of the sense of reality, a widening of the imagination". Truth is not always wanted she says. And concludes with "the truth is balance, but the opposite of truth, which is unbalance, may not be a lie".Viewed from such a position, Györfi's video opens up to a wider horizon. Moving from a flirt with media and cultural codes to a play with roles that ultimately has something to do with truth. If we stick to the first schema of media codes, the work would be left kicking about on dry ground. Exactly the moment when the video goes blank just to let the lead singer reappear as a new character (of a lead singer) makes us aware of "the widening of the imagination". The objects found in the rest of the exhibition, on the other hand, gives us just a vague sense of Györfi's strategies of art production. There is a lounge with a turntable where you can sit down and listen to a vinyl single produced by Györfi, which features "China Girl" on the A side, and a version of The Stranglers "Hanging Around" on the flip side. The listening-station is surrounded by three crispy wall paintings of recording equipment: a microphone in its stand, an electric guitar, a reel-to-reel tape recorder. These icons don't seem to add anything significant to the reading of the work, but indicate a fetishististic fascination with the aesthetics surrounding a production of this kind.

Backdrop 3:

The artist as . . . if

Benjamin contrasted his ideal producer with the routinier, the author who merely supplies the productive apparatus without improving it. One does not necessarily have to subscribe either to Benjamin's Marxist stance or to Graham's Situationist tenet in order to share their dreams of an art that manages to establish an alternative model. One may, for example, dream of an art that does not, bluntly put, sit on its ass on some minimalist sculpture, claiming smugly that it thereby increases the use-value of minimalism.